Submission Draft.

Project #2: Environmental Autoethnography

Metacognitive Reflection

850 words

I chose the environmental autoethnography project for the submission draft because I have been learning more (compared to the previous environmental inquiry project) throughout the entire writing process. Being completely new to the genre of autoethnography, I started the writing process with my naive understanding of “detailed depictions.” I had no idea about what autoethnography was, and I only got little idea after reading about Rush’s book Rising. However, after learning more in class and reading other good autoethnography pieces, I started to like this new genre because of its effectiveness and “thick description.” I revised my planning and the elements used based on those new understandings, and I gained more confidence after receiving positive feedback from my peers and the professor. I found the entire writing process especially comprehensive because unlike the previous project, which I was pretty familiar with the genre of inquiry projects, I’ve learned something entirely new for me and made progress step by step throughout the process. That makes it particularly suitable for my ePortfolio and its theme “Plan, Learn, and Revise” – those three words precisely sum up the entire writing process throughout the last four weeks.

As mentioned above, I started the writing process with completely no idea about the genre of autoethnography. I took some practice about “detailed depictions” at the beginning of the process, and that gave me some ideas about what I was going to do next. As I read Rush’s book Rising as a template of autoethnography, I found this genre was particularly effective in presenting issues to the readers. Its detailed and compelling narration can easily make readers reflect more on the topic. I built a plan at the beginning of the second week of the writing process, which set my project’s fundamental structure. As I learned more from other sample autoethnographies, I revised my plan in order to implement my own “thick description” more appropriately. Unlike other projects, the initial draft of this project took me quite amount of time because I need to sit down and extract as much detail as possible from my childhood memory to build my “thick description.” Because I spent a significant amount of work to ensure my narration as detailed as possible, I’ve been incredibly confident about the part of my personal experience throughout the writing process. The positive feedback from my peers about my narration also increased my confidence in that.

In the stage of revising and editing, my main priority was the central focus and the organization of my article. I was not very confident about the effectiveness after finishing the initial draft. The feedback from my peers also confirmed that the focus was a weakness of the article. The professor also provided me some feedback on that, suggesting move paragraphs around to make my writing more effective and lead with primary research over secondary sources to highlight the priority of my primary research. All those suggestions from peer feedback and the professor’s conference were addressed when I composed the submission draft. I appreciate those constructive and helpful suggestions as they let me know my project’s strengths and weaknesses and how I should address them in the next draft.

For the final product, I feel like one of its strengths is the narration about my personal experience. As mentioned above, I’ve spent a lot of time composing and polishing it to make sure it contains as much detail as possible. I’m also confident using others’ voices to implement a comprehensive “thick description” in the article. Specifically, I used my parents’ voices to provide some historical details on the issue, and I used several secondary sources to make the stories connected and provide voices from scientists. The possible weakness of the final product includes the central focus and the overall structure of the article. Although I have been trying to improve the structure by moving things around, new issues might be created and not observed throughout the revision process. Source attribution and clarity have also been some weaknesses for me throughout the entire revision process. I’ve checked the submission draft several times to ensure there will not be any low-level errors in my final product.

Overall, my work on the environmental autoethnography project reflects a learning process to write something entirely new for me – the autoethnography. It shows that I could quickly learn a new genre by reading books, learning from the class, and reading other sample articles. It also represents my ability as a writer to revise my planing throughout the process. I got a deeper understanding of the task and the genre, and I received constructive feedback from my peers and the professor. I’ve learned a lot throughout the process. Besides this new genre of autoethnography, I’ve also learned the importance of planning, revising, and providing feedback in the college-level writing, as well as the necessity of recognizing the strengths from other readings and implementing those shining points into my own article. I enjoy this process of learning and writing, and it will serve as a template for me to try other new genres in the future.

Feedback Files

Submission Draft

1492 words

Disappearing Coastlines

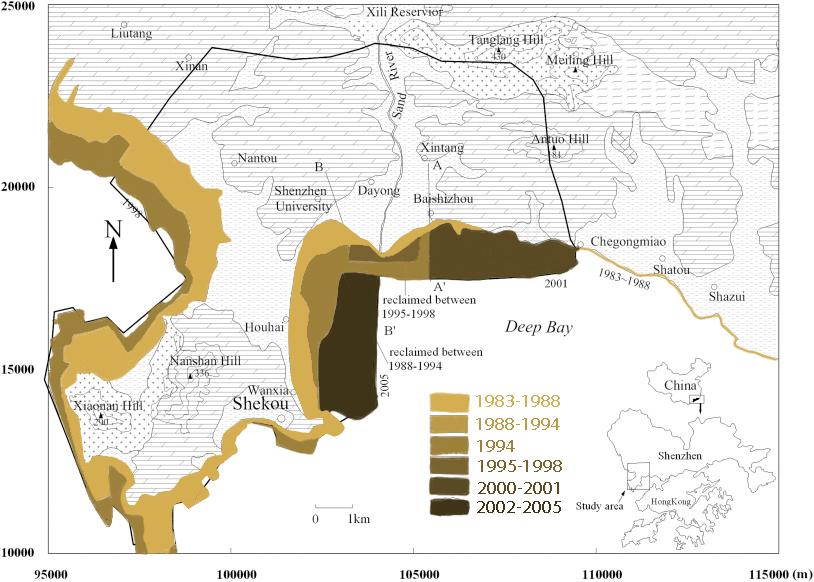

Shenzhen, a city rested on China’s southern coast, has been one of the fastest-growing Chinese cities since the 1980s. Its GDP per capita grew over 24 times from 1978 to 2014, and it’s currently still one of the fastest-growing cities in the country (Kenton, 2020). According to a news report by Wang, the city holds over 10 million people on a land of about 2000 square kilometers, making it one of the most crowded cities in the country as well. More than 69 square kilometers were created from the sea through land reclamation, and the city plans to reclaim 50 square kilometers more in the next ten years (Wang, 2016). Most of those newly created lands are distributed to a district called Nanshan, where is the home of many famous tech companies such as Tencent and Huawei. It can be said that the city’s development has relied on land reclamation in the past 30 years.

Hundreds of skyscrapers and residential buildings are built on the reclaimed land, and those have become offices and homes for hundreds of thousands of white-collars in the district. My parents are among them. As a result, I’ve been living in the district of Nanshan for more than twenty years. If you take a look at Google Maps, my home is pretty much at the district’s center. But believe it or not, thirty years ago, it was located on the coastline of the city – basically just minutes of walk away from the ocean. When my parents decided to buy our home at that time, a slogan was on the advertisement of the apartment building: “The most comfortable apartments with the best seascape.” That description from the developer was actually accurate: when my parents moved in, the ocean could be directly viewed from the windows. My mom once showed me the photo on that spectacular view she took on the move-in day. “I really loved it,” she said, pointing to the photo, “when Hong Kong hadn’t returned to China yet, there were even sentries on the street downstairs – our home was so close to the border. It was like a three-minute walk from the coastline, and across the bay, it was Hong Kong.”

I didn’t have a chance to see that with my own eyes. I was born five years after my parents moved there, and since I started to remember things at about five years old, that spectacular view of the ocean has disappeared. The coastline was pushed forward, and our home was surrounded by cranes and construction sites. The sea view was obstructed by the newly constructed buildings. Though I could still see the sea through the gap between those buildings, that view could not deserve the title of “the best seascape” anymore. The coast was cordoned off as a reserved area for the land reclamation project, but I still liked to go there to take a walk with my parents or play the toys with my friends. I loved the delightful smell of the ocean, and I enjoyed the feeling of the sea breeze. When the weather was good, I could fly a kite with my friends – that was really one of my best childhood memories.

However, those good times didn’t stay long. More and more bulldozers and excavators occupied the coast, and trucks full of soil came in to reclaim the land. Things drastically changed in the following years. The ocean view completely disappeared from my windows – it was replaced by the view of skyscrapers, office buildings, overpasses, and shopping malls. In less than five years, the coastline was pushed forward by more than three kilometers (about two miles). The delightful sea breezes disappeared, and they were replaced by the smell of automobile exhaust and the noise of impatient vehicles. Because of the construction sites and the new buildings, I could no longer take a brief walk to see the ocean. I would need a 40-minute walk instead of a five-minute one several years before. Roads were widened around my home, and my parents would always remind me to be careful when crossing the streets because the traffic got much heavier in the area I resided. By the year that I finished primary school, a fully functional CBD (central business district) had been built on the newly reclaimed land. It became the center of business, recreation, shopping, and transportation for the district’s residents.

But the city has to pay the price for it. The environment on the coast was irreversibly damaged, and my father witnessed that damage. As a passionate photographer of seagulls, he loves to come to the seaside to take seagulls photographs whenever he has spare time. This habit started when I was very young, and he was always able to take many fantastic photos of seagulls and show those to us with joy. But year by year, as the reclamation project went on, he found it became harder and harder to take good photographs of seagulls. The seaside became hard for him to access, and even he came near the coast, it would take more than several hours for him to find a proper shooting angle because most of the seagulls were gone. Even with the most advanced telephoto lens, the photo he took couldn’t match the quality with the ones that he took years before. Since then, he often came home with sigh and disappointment. He would rather drive an hour to visit the coast on the other side of the city to take the photographs for seagulls because he felt he would waste tons of time waiting for the seagulls. His feeling was right. According to a report by Wang et al., the mangrove forest in Nanshan district, which is one of the most famous ecological areas in the city, was seriously damaged by the land reclamation project. The total mangrove area was drastically reduced, which basically had destroyed the habitat for migratory birds. The ecological diversity on the coast was thereby diminished (Wang et al., 2014).

Besides, water pollution is also a by-product of the land reclamation project. When I was in middle school, I liked to go cycling with my friends. The government had built a recreational park near the coast, so it was convenient for us to ride our bikes there. But still, when we ride near the sea, we usually had to cover our noses because the smell of the sea was really uncomfortable. The water’s color could even change every time we came there: sometimes it was yellow, occasionally green, and other times it could be red. Research has shown that the water on the coast and the groundwater under the peninsula were seriously affected by land reclamation (Hu & Jiao, 2010). In particular, Chen and Jiao’s study has suggested that the flow of groundwater was distorted, and its level of heavy metal elements had increased after the land reclamation. Although the groundwater was not used for either drinking or industrial purposes, the study found that most of those heavy metal elements would eventually go to the sea and affect the coastal environment (Chen & Jiao, 2008). Those water pollutions not only made the visitors uncomfortable, but more importantly, they seriously damaged the habitat for the fishes and birds that had lived on the seacoast before (Wang et al., 2014).

Fortunately, more and more people started to realize the seriousness of those environmental impacts and appeal for a more environmentally responsible land reclamation planning. As responses, the government built a mangrove nature reserve along the seaside and put strict regulations for visitors (Tam, 2010). Nowadays, visitors are not allowed to enter the reserve to ensure the last and the only habitat for migratory birds is protected (Jia et al., 2016). Some experts have suggested that the government should imitate Hong Kong, the city across the river facing the same land shortage issue, to completely ban any further land reclamation (He, 2019). But undeniably, land reclamation can be the easiest solution to many societal problems like the rise of house prices. As one of the most crowded cities in the country, Shenzhen has suffered from an explosion of house prices (with a year-over-year increase of over 70 percent in 2016), and it desperately needs more land for development (Wang, 2016). As a result, the city must accept this challenge and develop an equilibrium between its rapid growth and environmental protection. The disappearing coastlines and all subsequent environmental impacts are the prices that the city has paid for its endless land reclamation. The authorities, along with the citizens, have to work creatively to address this challenge. In front of the skyline of the prosperity, I hope, in one day, I can witness the return of seagulls and clear water along the coast – that is ultimately the most beautiful scene that we can have in my dear hometown Shenzhen.

Bibliography

Chen, K., & Jiao, J. J. (2008). Metal concentrations and mobility in marine sediment and groundwater in coastal reclamation areas: A case study in Shenzhen, China. Environmental Pollution, 151(3), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.04.004

He, H. (2019, January 2). Hong Kong, Shenzhen reclamation plans may be on collision course. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/2180273/hong-kong-shenzhen-multibillion-dollar-land-reclamation-plans.

Hu, L., & Jiao, J. J. (2010). Modeling the influences of land reclamation on groundwater systems: A case study in Shekou peninsula, Shenzhen, China. Engineering Geology, 114(3-4), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2010.04.011

Jia, M., Liu, M., Wang, Z., Mao, D., Ren, C., & Cui, H. (2016). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Conservation on Mangroves: A Remote Sensing-Based Comparison for Two Adjacent Protected Areas in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, China. Remote Sensing, 8(8), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8080627

Kenton, W. (2020, January 29). Shenzhen SEZ, China. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/shenzhen-sez-china.asp.

O’Donnell, M. A. (2013, April 30). edgy map. Shenzhen Noted. https://shenzhennoted.com/2013/04/30/edgy-map/.

Rodney. (2018, February 24). Coastal City Nanshan. Shenzhen Shopper. https://shenzhenshopper.com/73-coastal-city-nanshan.html.

Tam, F. (2010, July 12). Reclamation threatens last of Shenzhen’s coastline. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/article/719552/reclamation-threatens-last-shenzhens-coastline.

Wang, J. (2016, March 4). Shenzhen eyes land reclamation to curb rising housing price. China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-03/04/content_23738729.htm.

Wang, W., Liu, H., Li, Y., & Su, J. (2014). Development and management of land reclamation in China. Ocean & Coastal Management, 102, 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.03.009

Zhou, Y., Bai, J., Zuo, T., Liang, J., Xiao, H., & Zhou, Q. (2018, September 26). Tegao: Shenzhen tianhai sanshinian (shang) [Feature: Thirty Years of Land Reclamation in Shenzhen (Part 1)]. The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2473058.